Nahray Crisden was his mother’s greatest blessing when she gave birth to him on Sept. 16, 2000 after struggling with serious health issues for most of her life. For his middle name, she chose Munakk, which means “savior” in Arabic.

And Nahray lived up to that name. He tried to save the young men in his neighborhood who were hungry, temporarily homeless or emotionally numb. Exuding a quiet strength, he offered them clothing, snacks, a place to crash, and a surrogate family with his mother and grandmother.

“He never treated anyone different for having less than,” remembered Nahray’s mom, Rashala St. Hill. “He was genuinely a friend.”

One of Nahray’s closest friends from second grade, Sean Brown, called Rashala “mom” and lived with the family for more than a month. Rashala and Nahray’s grandmother, Deborah Ossai, fed and dressed Sean, gave him spending money, and registered him for school.

On Sept. 13, 2020, Nahray and Sean were hanging out in Deborah’s basement in Overbrook Park, playing games and drinking sodas. Later, they took a walk to a Conoco station on City Avenue to buy snacks. Nahray was smiling and appeared carefree, according to the surveillance video. Sean was wearing the red New Balance sneakers that Rashala had bought for him.

As they were walking back, around 10:45 p.m., Sean pulled a gun on Nahray while he had his back turned, eyes glued to his cell phone. Nahray was shot in the torso six times and found dead on the 1400 block of Surrey Lane in Lower Merion.

In November of 2021, Sean, 20, was sentenced in Montgomery County Court to 19 to 38 years in prison after he admitted to killing his childhood friend.

Sean never apologized to Nahray’s family or gave them an explanation, Rashala said.

“I don’t hate you,” she told Sean in court, “but I’m very disappointed in you because you could’ve done better.” She offered to respond to his letters from prison, but she has yet to receive one.

Nahray, also known as “Ray,” spent much of his life with his mom in Southwest Philadelphia and with his grandmom in Overbrook. Though he didn’t have any close siblings, Nahray called his uncle, Dedrick Francis, his “twin” because they were only one year apart.

As a baby, Nahray zipped around the house with abandon. By the time he was 10 years old, he was considered the fastest kid in the neighborhood, Deborah recalled.

Nahray was naturally gifted at every sport he tried — football, track, soccer, or tennis.

He attended the West Philadelphia High School Promise Academy and helped the West Philadelphia Speedboys go to the state championships for the first time in more than 40 years, Rashala said.

The team nicknamed Nahray “bullet” and his coaches raved about his speed and respectful demeanor.

In the off-season, Nahray ran track and his coaches persuaded him to continue to see if he could win a college scholarship. Nahray went on to break a record in the Penn Relays, Rashala said.

From the time her son started to talk until high school, Rashala made him recite every day: “You will not visit me in a jail cell. You will visit me in a college dorm.”

“Ray was leaning toward doing anything that would make him successful,” she said, adding that he wanted to buy her a house in recognition of her sacrifices as a single mother.

She called him “toots,” for Tootsie Roll, because he was so cute and chocolate brown. They enjoyed dining at Nifty Fifty’s, where he would always order the most elaborate milkshake.

Nahray was protective of Rashala, yet wasn’t jealous when his friends called her mom. Hers was the “cool house,” where everyone felt safe. Trusting and generous, Nahray would give away his clothes if a friend needed them more.

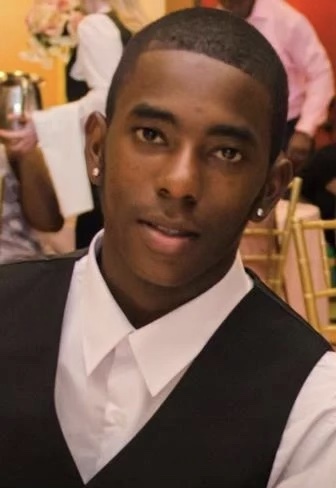

Handsome with flawless teeth, Nahray always had a girl on his arm. His arms were tattooed with his mother’s and grandmother’s names, along with “loyalty and dedication” to represent his devotion to sports.

If track or football didn’t pan out, Nahray considered joining the Navy to see the world. At 18, he transferred to YouthBuild Philadelphia Charter School to learn construction and real estate.

“It doesn’t matter what way I make it,” he told his grandmother Debbie. “I just want to make it out.”

Nahray and his grandmother used to sit at Debbie’s kitchen table, drinking coffee together or eating her homemade spicy pickles.

He enjoyed rapping under the name Ray-Mac, which was also his father’s nickname. Rashala eventually convinced Nahray that “King Ray” was a better fit.

When Nahray was in the ninth grade, he saw his estranged father in a store buying balloons for his new daughter, Rashala remembered. That year, she made sure to buy Nahray $100 worth of balloons for his birthday, along with cupcakes for the entire football team.

Nahray’s grandfather, Tommie St. Hill, had been a reporter for The Philadelphia Tribune and Nahray inherited his appreciation for the written word. He wrote lyrics and letters asking why his father, who had four other children, didn’t love him. Nahray looked forward to having his own children so that he could be a better dad, his family said.

“There was poetry to his words that made it work with his music,” Debbie recalled. “Nahray was very talented and it’s so sad to see it all shut down.”

Nahray is buried in Fernwood Cemetery. Debbie credits the Lower Merion Police Department for their steadfast commitment in solving her grandson’s case; she bought all the detectives patterned socks.

She and Rashala have plans to open up a group home for troubled boys called “Ray’s House.”

Rashala now fosters two young boys, ages 8 and 12. She believes that Nahray sent them to her.

“I took them because even though Sean ruined my life,” she explained, “he’s not about to ruin my soul, too.”

Resources are available for people and communities that have endured gun violence in Philadelphia. Click here for more information.