Born the day before Mother’s Day on May 9, 1998, Kevin Selby turned himself into jelly whenever his mom tried to hold him in her lap, wriggling out of her arms.

That independent streak defined much of his short life. As a child growing up in North Philadelphia, and later, Mayfair, Kevin memorized bus routes and subway maps so that he could hang out at a Target or a dollar store across town.

“He would go anywhere and he was fearless about it,” remembered his mother, Lenaya Abron.

Kevin had a strained relationship with his father, who was in and out of his life, so he sought refuge with the most important women in his life — his mother, his aunt, his godmother, and grandmother. He also had three sisters — China, Malikah and Sarah.

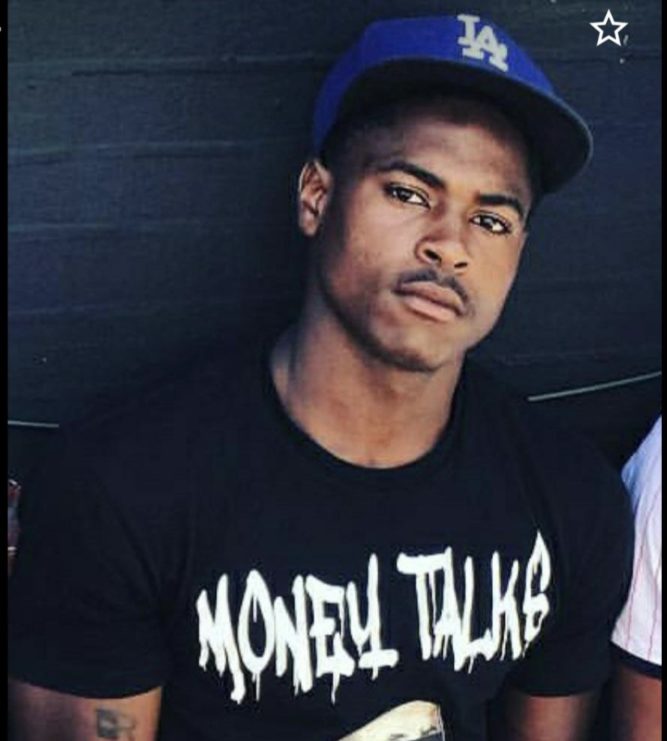

Charming and athletic, he quickly transformed from the “icky little brother” to “ooooh, that’s your brother?” among China’s older friends. Kevin was such a popular prom date that Lenaya bought him a suit to wear on rotation. By the end of the night, her son had made friends with everyone, including the DJ.

Even the elderly women on the block adored Kevin for walking their dogs, running errands, and escorting young female relatives on the bus back home. “That’s my boyfriend,” the neighborhood’s matriarchs would call to the blushing boy.

But Kevin couldn’t sit still for long and he yearned to fit in, after being diagnosed at young age with Asperger’s syndrome, an autism spectrum disorder.

On July 5, 2020, he was attending an Independence Day cookout on the 2100 block of East Ann Street in Kensington. Sitting outside, the 22-year-old was shot multiple times. Kevin died at Temple University Hospital during a holiday weekend marred by at least 17 shootings across the city.

Police charged the shooter and an accomplice in connection with Kevin’s death but they are still awaiting trial, Lenaya said. She believes that her son was targeted, but she does not know why.

“At least somebody else’s son is going to survive a little longer because they’re in jail,” she said, flatly.

Kevin was Lenaya’s special boy. By five years old, he was already parroting back terminology on the lymphatic and cardiovascular systems from his mother’s nurse training CDs.

Despite being whip-smart, Kevin struggled at People for People Charter School in North Central Philadelphia. His teachers threatened to hold him back because he refused to take notes yet regurgitated his assignments effortlessly, Lenaya remembered.

When asked to spell the word, “wood,” he astutely responded, “Would as in the question or wood as in the tree?”

It became clear that the young boy required extra support to help him make sense of the world.

After he turned eight years old, Kevin was diagnosed with Asperger’s. He continued to be teased for being slow, but he did not register it on an emotional level, Lenaya said.

Instead, he fixated on mastering tasks, such as drawing. He obsessively changed the laces on his sneakers and brushed his hair constantly because he desired waves. Shrill voices disturbed him, as did barking dogs, so he popped in his earbuds to drown it all out with the oldies or hip hop.

As he got older, Kevin grew more embarrassed by his diagnosis and took great pains to hide it from his friends lest they think he was “crazy” or “stupid,” his mother said. He went out of his way to befriend people who were misunderstood like him.

“Kevin wanted friends so bad that he would give away his video games. He had nothing to play with,” recalled his godmother, Brenda Brown, who took in Kevin when he was around nine years old and again shortly before his death.

Kevin was respectful to his elders and a good listener, reciting everyone’s birthdays. He also collected football cards and memorized players’ stats, which made him a formidable opponent during sports debates.

He was a jokester, convincing younger kids to scarf down habaneros because they weren’t really that hot. He enjoyed social media spoofs and was especially fond of one in which a fake Lebron James takes his teammates’ championship rings because they didn’t do any work in the game.

“Gimme your ring” became his inside joke.

“He would tell smart people jokes and you would get it later,” Lenaya recalled.

But Kevin also became easily enraged, caught in the revolving door of inpatient behavioral treatment programs until he was old enough to opt out. He sliced his arms with razors and wore long sleeves in the summer to hide the evidence. He set fires in his mother’s apartment. He memorized the engraved numbers on the back of psychiatric drugs but refused to take them.

While Kevin acted as if he didn’t care about his fair-weather father, he became visibly upset when his dad missed a scheduled dinner, Brenda recalled.

Though he lacked academic focus, Brenda convinced him to complete two days of homework in one sitting so that he would have more time outside. For a period, his grades improved.

Kevin played basketball and varsity football at Upper Dublin High School in Fort Washington but never graduated. When Lenaya encouraged him to join a community league and finish school, Kevin informed her: “I’m grown.” Still, he refused to stop wearing his old, ill-fitting football equipment.

Kevin could have been a model, Lenaya said. “He had prettier lashes than me.” Instead, he took a part-time job at UPS and relied on marijuana to dull his explosive anger. He spent short stints in jail for petty crimes, Lenaya said, and the judicial system refused to address his behavioral health issues.

After growing up Baptist, Kevin decided to become Muslim like his father. Mourners recited the traditional Janazah funeral prayer and Kevin was cleaned, wrapped in a shroud and buried facing Mecca in Chelten Hills Cemetery in the West Oak Lane section of the city. At his funeral, Kevin’s friends reminisced about how he used to wake up homeless people on the street to hand them money or food.

A few months after his son’s death, Kevin’s father died of cancer.

A few days before Kevin was killed, he spoke about changing directions, Lenaya remembered. He was tired of hanging out with the same negative influences.

“He was really in the stage of trying to find out what were his strengths,” she said. “He hadn’t gotten that far yet.”

Resources are available for people and communities that have endured gun violence in Philadelphia. Click here for more information.

Date: 2020-07-05

Location: 2100 Anne St, Philadelphia, PA

Leave a Reply