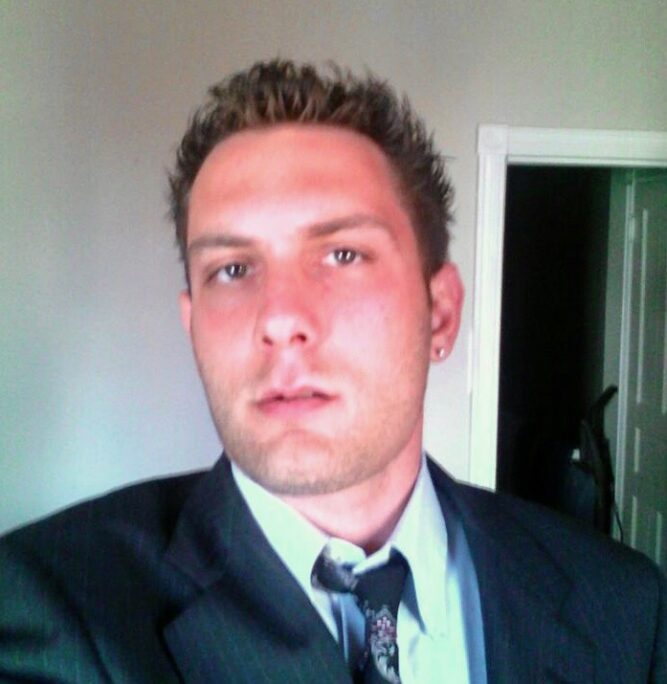

On the outside, Jeremy Pizzichil was an insatiable entrepreneur and a born salesman, a mix of Batman and Jordan Belfort from “The Wolf of Wall Street” with a chiseled jaw, dazzling hazel eyes, crisp suits, and a propensity for living on the edge.

“FAST CARS, FAST BOATS, FAST GIRLS, FAST LIFE,” he proclaimed on his Pinterest page. “IT’S not the cards you were handed, IT’S how you play them that counts,” he reminded his 4,400 Facebook friends.

On the inside, however, Jeremy knew he had been dealt a rotten hand. Beholden to the numbing trio of crack, heroin and alcohol, he craved stability and unconditional love, haunted by the suicides of the three women who had raised him — his mother, grandmother and aunt.

“He probably went through life thinking that he didn’t matter,” said his cousin, Gail Scott, explaining that Jeremy was passed around among family members in Florida and in the Philadelphia area, and became a ward of the state in Pennsylvania before he sought redemption on the streets.

In 1998, Jeremy’s mother, Cheryl Pizzichil, who struggled with drug addiction, wrapped herself in a blanket and shot herself in a back stairwell of their apartment while the 12-year-old was downstairs watching television. It took days before family members could locate her body.

Four years later, Jeremy’s grandmother, Cecilia Pizzichil, described as a positive guiding force in his life, bought a pack of cigarettes from Kmart and threw herself into the path of an Acela train in Bensalem.

In 2015, Jeremy’s aunt, Frannie Kaiser, with whom he had lived after his mom died, hanged herself.

“You never knew what to expect from Jeremy,” Gail remembered. He “wanted nothing but to love and be loved.”

She continued: “What I think Jeremy did was tucked [the pain] away somewhere and tried to do something that would make him feel good.”

On October 1, 2021 at around 11:30 p.m., Jeremy was fatally shot by a passing vehicle outside of a Wawa on the 1600 block of South Columbus Boulevard. He was 35.

A 24-year-old man was also shot in the foot but survived. Police have made no arrests.

By that point, Jeremy had succumbed to full-blown addiction, isolating himself from his extended family. Some only learned of his death months later through a Google search. They don’t know where — or if — he is buried.

“There’s another world inside of me that you may never see/There’s secrets in this life that I can’t hide…” (From “When I’m Gone” by Three Doors Down, posted on Jeremy’s Facebook page two months before his death)

Born in the Mayfair section of Philadelphia on July 29, 1986, Jeremy was raised by a single mother who failed to discipline him and treated him like an irritant — “she spoke at him and to him,” Gail remembered. When Jeremy was still young, Cheryl moved them to Florida to live with Jeremy’s grandparents, who doted on him.

Jeremy Pizzichil

Although Jeremy missed his old friends from Pennsylvania, he enjoyed riding bikes and performing handstands in the pool with his two cousins, Danika Scott and Geneva Brend. He delighted in showing a scary “Chucky” movie to the younger Danika, and convincing her that a blood pressure cuff was actually full of needles. He also taught her curse words in Italian.

When Gail, Danika’s mother, called him out on it, Jeremy shrugged: “What? She’s gonna learn it anyway.”

Jeremy was witty, but never condescending or insulting, Gail remembered. She nicknamed him “cool breeze,” because he brought the party with him.

Danika recalled Jeremy as the “sane one” of the trio. When Geneva wanted to jump in with an alligator, for instance, Jeremy kept her in check. If Danika fell down while they were playing a competitive game of basketball, Jeremy would stop to make sure that she wasn’t hurt.

“He did have a good head on his shoulders,” Danika said. “He had the confidence on the outside but not on the inside.”

Jeremy looked forward to sleepovers at the Scott home, which smelled of comforting marinara (gravy). The cousins would play Battleship and then be stuck watching Star Trek on TV because Danika’s dad was in charge of the remote.

At Christmastime, Gail made Danika, Geneva and Jeremy matching velvet-trimmed and plaid pajamas and invited all the neighborhood children over to bake misshapen sugar cookies and craft ornaments from photographs and plastic shower rings.

When Gail told Jeremy that she loved him, a look of surprise crossed his face. Then he wrapped her in a hug.

After his mom died, Jeremy lived with Frannie and Geneva in Florida’s Jensen Beach. Later, he lived with another cousin, until her boyfriend threw a beer bottle at him for misbehaving.

At age 16 with only a trash bag of stuff to his name, Jeremy became a ward of the state of Pennsylvania. Another cousin, Anthony Bianchini, offered to have Jeremy stay with him and his family in their large home in Langhorne, but there would be rules to follow. Jeremy had to keep up his grades, swear off drugs and alcohol, and no longer associate with his friends in Philly who were a negative influence.

During the family court hearing, Jeremy was furious, demanding to move back in with his cousins in Florida or live at a boys’ group home in Hershey. He relented, Anthony recalled, only after a social worker informed Jeremy that he could be abused at the group home.

During the year that Jeremy lived with Anthony and his family, he made honor roll every semester, ran track, received counseling, and drew abstract animals, flowers and symbols of death. Anthony ruled with a stern but loving hand, investigating and confirming Jeremy’s whereabouts.

Jeremy graduated from Archbishop Ryan High School in Northeast Philadelphia and Anthony offered to pay for his college. But after learning of his grandmother’s suicide, Jeremy’s rebellion only intensified.

“Nobody cares about me anymore,” he confided in Anthony one day.

“He had these demons that kept eating at him,” Anthony said.

After he turned 17 years old, Jeremy went off on his own. The last time Anthony spoke to him was in 2004, when a disheveled Jeremy came to visit Anthony’s father who was dying of cancer.

The following year, Jeremy was quoted in an Associated Press article about teenage orphans. He acknowledged that he had been “spinning my wheels, living on impulse,” before arriving at Christ’s Home in Warminster. He had hopped from staying with a friend’s family to a hotel to a homeless shelter, but was now managing his finances and studying to become an electrician.

“It works out for a few months, staying with friends and their families,” he told the reporter. “But you’re not theirs.”

Gail and Danika Scott only had sporadic contact with Jeremy after they moved from Florida, because, as Gail noted, he isolated himself and didn’t want to be found. At one point, they heard that Jeremy had been caught sleeping on his niece’s porch. Anthony learned that Jeremy had a son.

Jeremy “didn’t have the direction he needed to learn life on life’s terms,” Gail said.

His still-active Facebook page is an homage to the Mummers, Ferraris, guns and Independence Hall.

Jeremy sold cars before he got a DUI in South Carolina. His uncle helped him set up a business marketing medical supplies, Gail said, but it never took hold.

“He really wanted to do something big,” she explained, “and once he got to that point he wasn’t confident to [see] it to fruition.”

Jeremy’s friend and former co-worker, John, who declined to give his last name, recalled that Jeremy excelled at marketing pain creams and diabetic supplies.

“He was very much a go-getter,” John said, “always looking to do the next thing, build the next challenge.”

John and Jeremy discussed partnering in a medical sales business, but both kept ping-ponging from recovery to relapse.

Shortly before his death, Jeremy expressed interest in going back to rehab.

“I encouraged him to do it and was going to pick him up from the train station,” John recalled. “And he faded to black.”

A reward of up to $20,000 if available to anyone that comes forward with information that leads to the arrest and conviction of the persons responsible for Jeremy Pizzichil’s murder. Anonymous calls can be submitted by calling the Citizens Crime Commission at 215-546-TIPS. Information can also be submitted to the Philadelphia Police Department online or by calling 215-686-TIPS.

Resources are available for people and communities that have endured gun violence in Philadelphia. Click here for more information.