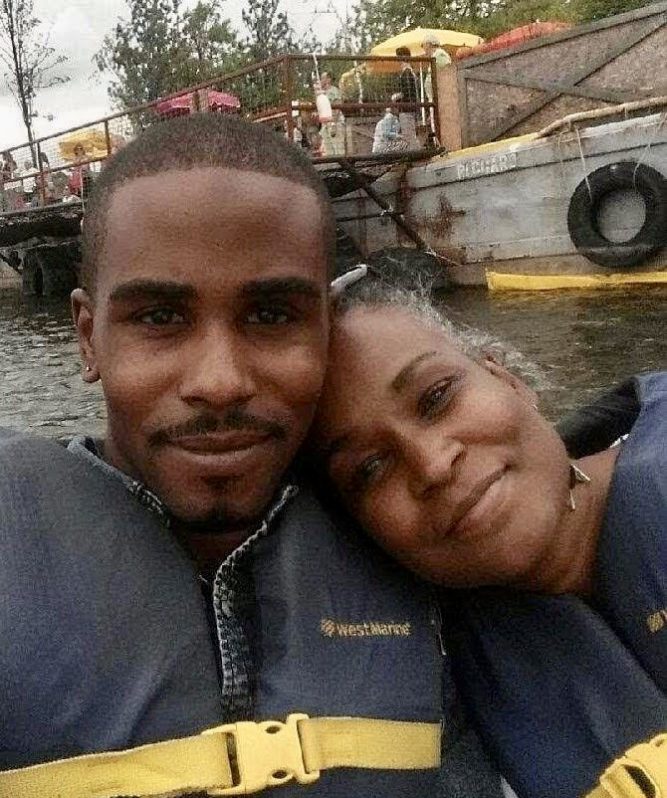

From an early age, Calvin Morton Greene understood the importance of knowing your history and creating generational wealth as a path to independence.

His mother, Tracy Morton, taught him that and so much more. While Calvin was still in utero, Tracy encouraged him to learn a second language to increase his career prospects. Go to church every Sunday to be rooted in faith, she counseled her toddler. If you can read, you can teach yourself anything, she told Calvin in elementary school. Buy clothes based on what you like and ignore the brand name, she advised her teenager.

As a result, Calvin was mocked for his Payless brand cleats by other players in his community football league.

“My mom is not stupid enough to pay $150 for a pair of sneakers that will just get muddy,” he retorted.

By the time he turned 20 years old, Calvin had already bought his first home — a five-bedroom property with off-street parking in North Philadelphia. He rented out the four other bedrooms and covered his mortgage, plowing the savings into other real estate investments.

“Do not rent a room out that you wouldn’t live in yourself,” Tracy instructed.

Later, Calvin and Tracy paid $13,000 for a residential shell in Frankford. Calvin taught himself how to install drywall, framing, electrical and plumbing. He also taught Tracy how to screen prospective tenants: Make sure they look you in the eye, provide pay stubs and dress well, he said.

But there was one lesson that Calvin didn’t learn in time: Anticipate trouble before it happens.

On Dec. 11, 2020, Calvin was on his way to help Tracy with a plumbing issue at her house and stopped to pick up breakfast for her at a restaurant in the 2900 block of North 22nd St. in North Philadelphia.

Another male customer was acting irate with the servers and bumped Calvin hard on the way out, according to surveillance footage viewed by Tracy. Words were exchanged. The video shows Calvin walking to his car and then walking to the man’s car nearby. That is when the man got out of his car and shot Calvin three times. He died instantly.

“That’s the only solace I have from the way it happened,” Tracy said. “He literally put him to sleep.”

Calvin’s body was cremated and his memorial service was delayed by seven months due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Police charged Kalib Hurst, who had a tattoo of a gun on his forearm, for Calvin’s murder. He is in jail awaiting trial.

Calvin had planned to move to Atlanta in the next few months with Tracy to grow his real estate business.

“He wanted to go big with it,” recalled his aunt, Teasa Gill. “He had already made his mark in Philadelphia.”

Calvin was proud to take care of his mother, picking up her groceries and making sure that she had reliable transportation. He also went shopping with her; Tracy would select one item and Calvin would assemble the rest of the outfit for her.

There’s nothing wrong with being a “momma’s boy,” both reasoned, because it just means that “you take care of your mom.”

Calvin’s generous spirit extended to other family members. “If he had it, they had it,” Tracey remembered.

After Calvin made a surprise overnight visit to Teasa’s house in Atlanta, he left her $40 on the bed to thank her. One week before his death, Calvin sent Teasa’s husband, a huge Eagles fan, four crisp white Eagles caps. They remain in pristine condition.

Calvin was not into sports at all. While working at a nightclub, he tried to stop then-Eagles wide receiver DeSean Jackson from entering because he didn’t recognize him, Tracy recalled.

Calvin’s former girlfriend, Isis Brown, remembers him as financially savvy and romantic. Unprompted, he opened doors for her, brought her flowers and woke up at 5:30 a.m. to drive her to Feasterville for work.

The two met one night when Calvin was Isis’ Lyft driver. After picking her up from IHOP in Port Richmond, where Isis worked, Calvin offered to give her daily Lyft rides in exchange for IHOP food. They struck a deal.

Although Calvin was ten years her senior, Isis was impressed by his ambition. They dated for three years, during which time Calvin counseled Isis on how to create a budget while paying off her student loans. The two discussed getting married and raising a family, but Calvin wanted to be on firm financial footing.

“Separate your needs from your wants,” he told Isis. “Then pick two or three wants you can still afford until you get to the next level.”

“He always wanted the best for whoever was in his life,” she remembered.

Born on July 8, 1988, Calvin grew up in East Oak Lane and enjoyed tinkering with anything mechanical at a young age. He installed a radio at the front of his bicycle and rode around listening to R&B.

When he was just 13 years old, he worked as a suit salesman — “wear a suit for an interview. I don’t care if you’re going to work at McDonald’s,” Tracy instilled in him — but he quit that job because he thought he deserved a higher wage.

He moved on to fixing cars. Fidel Akor took him under the hood at his mechanic shop and stepped in as a protective father figure. At the time of Calvin’s death, he owned five cars, including a heavy-duty pickup truck with gargantuan tires, a Chevy Malibu, and a Scooby Doo-type van with fur cushions.

After graduating from YouthBuild Philly, Calvin set specific goals for himself: Learn the masonry trade, score a job at a top security firm and travel as much as possible.

He ticked them off one by one, enrolling in the proper training courses. He worked as a mason, took a job as a security guard for AlliedBarton, and became an American Airlines gate agent, allowing him to plane-hop from Philadelphia to Louisiana to Texas to Georgia.

Sometimes, it seemed like he was going one step forward, three steps back. He felt harassed by Philadelphia police officers on the streets but refused to tell them that his father was a police detective. Calvin had a strained relationship with his father, but the two became closer during the last several months of Calvin’s life.

While Calvin made acquaintances easily, he struggled to maintain close friendships because he was not a follower and others were jealous of his success. He had a temper and could hold a grudge, family members said, but he also encouraged those he loved to calm down and not take things too seriously.

Teasa recalled Calvin’s hilarious impression of TV personality Wendy Williams and her catchphrase, “How you doin’?,” his piercing brown eyes that seemed to burrow into your soul, and his massive sneaker collection — many with the tags still attached.

A month before he died, Calvin surprised Tracy with a bouquet of artificial red roses, destined to become her “everyday roses.” Just because.

“I didn’t have to call anybody for anything but him,” she said.

Resources are available for people and communities that have endured gun violence in Philadelphia. Click here for more information.