Brian Madera was living large and proud, sometimes grossing $7,000 a week driving his 18-wheeler, Big Bertha, and blowing nearly half of it in one weekend at the club.

He took frequent vacations to the Dominican Republic, where his family was from, and would blare Bachata music when he showed up for work at 2 a.m. He was a self-described “pretty boy” with a husky build, piercing green eyes, and the kind of sweetheart personality that offered to fetch a lady anything she might need.

Still, friends and familiy feared for Brian’s safety as he partied later in the night amid Philadelphia’s surging gun violence.

“He kept saying, ‘I don’t have enemies. Nothing’s going to happen to me. I’m Brian Madera,’” recalled his younger sister, Merily.

But a couple hours before dawn on Sunday, Dec. 5, 2021, Brian and Angel Luis Torres III, his friend from middle school, were fatally shot after leaving an after-hours club, El Vacilon, in the 3200 block of Front Street in Fairhill. Both were 22.

Brian’s 21-year-old cousin was seriously injured in the drive-by shooting but survived. Police have not made any arrests.

The following week, Brian had planned to set up a joint truck driving business with his longtime friend, Issael Rosado.

“He was on top of the world,” remembered Issael, who described Brian as a “happy soul.”

Born on Sept. 30, 1999 in New Brunswick, New Jersey, Brian spent most of his life living with his parents and sister in North Philadelphia.

To avoid having to go to daycare on the weekends, Brian woke up at 6 a.m. to help his father shop for his corner store. Domingo Madera gave his son $20 per shift, which the boy promptly spent on Nikes and biweekly haircuts.

When he was in the fifth grade, Brian coerced Merily into escaping their daycare while the other kids were eating in the cafeteria. They met outside at 3:35 p.m., grabbed hands and ran all the way home. After their mother was notified, she reluctantly agreed to let Brian babysit Merily if he promised to look out for her. Merily still remembers the delicious nacho cheese Doritos sandwiches that her brother made for her.

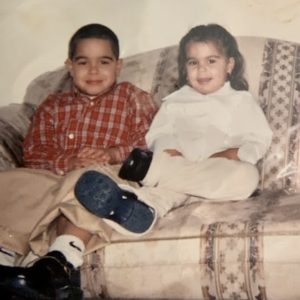

Brian and Merily as children

He nicknamed her “Nana” and was fiercely protective of his baby sister. Boys at school who looked at her better cast their eyes elsewhere, he growled.

Merily and Brian looked a lot alike, yet he teased her that he was “cuter” because she got stuck with the brown eyes. Play-fighting was their Olympic sport: He pinged her in the face with his BB gun and she dumped hot water on him.

After Brian fell off his bike in seventh grade, he was in a coma for more than a week. Merily recalled grabbing his hands in the hospital, willing him to wake up.

“Please, do it for me,” she pleaded. “I promise I won’t bully you anymore.”

Her brother stirred. To Merily’s amazement, he replied: “I’m not going to leave you by yourself.”

Talented at baseball and basketball, Brian could scarcely sit still after the accident. He worked six days a week, saving up $10,000 to buy his first car, a Honda Accord, when he was 16. He refused to ask his parents, a housekeeper and a shopkeeper, for any luxuries.

After graduating from Lincoln High School, Brian immediately studied to get his commercial driver’s license and began driving box trucks. Just before his 21st birthday, he had saved up enough to buy his own truck and trailer. His company logo was his initials — BHM.

Brian and Issael spent hours on the phone in their separate truck cabs during long hauls. Brian was hard-working, charismatic and silly, Issael remembered, the social connector among their close group of friends.

One time, Issael was fixing an electrical issue in his truck when Brian sneaked up behind him and slammed on the horn so hard that it knocked Issael over.

“If you fell, he would pick you up,” Issael said. “After he picked you up, he would make fun of you.”

Brian was unapologetically independent, even though he continued to live in the family home. He had no patience for being told what to do, Merily recalled, and often argued with his mother, Mercedes Basilio, over his spending and erratic schedule that kept her up at night.

Brian Madera

He kept his eyebrows and beard untamed, rode dirt bikes, splurged on Christian Louboutin shoes, and wore a Cuban gold necklace with a Buddha charm representing prosperity. He was proud to be an American citizen, indulging in Dominican rice and beans and Buffalo Wild Wings. One day, he imagined, he might move to Miami to be closer to the beach and start a family.

The night before Brian ventured out to the club for the last time, Issael told him and a few of their other friends to slow it down and start saving money to weather dry spells at work. In a rare burst of physical affection, Brian hugged Issael, kissed him on the cheek and told him he loved him.

“Yeah, bro, this is my last time,” he insisted.

That Saturday night, Brian pretended to go to sleep so that his mom wouldn’t worry. He slipped out after midnight to join his friends at the club.

Hours later, Merily was optimistic when she arrived at Temple University Hospital.

“You don’t know who he is,” she reminded her mom. “He’s Brian Madera.”

Then the doctor came in and told the family that Brian had died. Her parents, who don’t speak English, looked at Merily’s livid expression and knew.

Brian is buried in Greenmount Cemetery. On the day of his funeral, one of his friends drove Big Bertha behind his hearse. Inside Brian’s truck, sat an empty bag of Cheetos and Ray-Bans dangling from the rearview mirror.

“Your opinion is not going to kill me,” Brian would remind those who questioned his lifestyle. “If you don’t live happy, what are we going to do? Die sad?”

A reward of up to $20,000 if available to anyone that comes forward with information that leads to the arrest and conviction of the person responsible for Brian’s murder. Anonymous calls can be submitted by calling the Citizens Crime Commission at 215-546-TIPS. The Madera family is offering an additional $30,000 reward.

Resources are available for people and communities that have endured gun violence in Philadelphia. Click here for more information.